Pancreatic Cancer Breakthrough: Immune Cell Activation

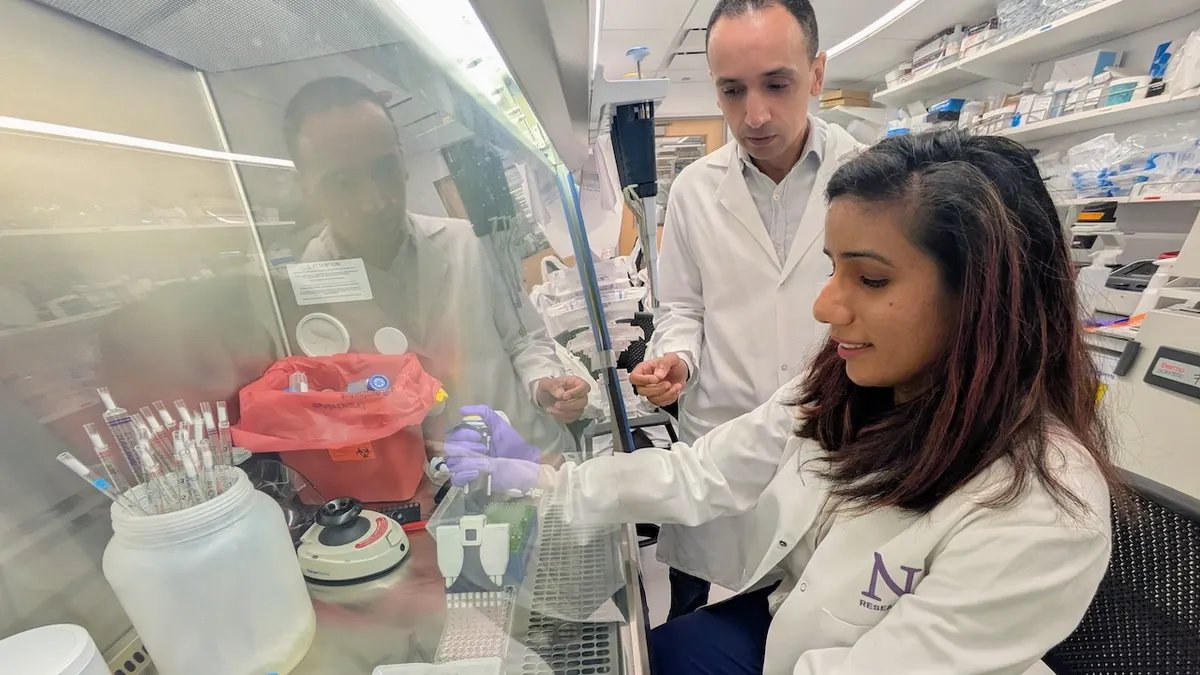

A groundbreaking development in pancreatic cancer treatment offers new hope by targeting the sugary shield that cancer cells use to evade the immune system. Researchers at Northwestern University have pioneered a novel antibody therapy designed to “wake up” immune cells, enabling them to recognize and attack pancreatic cancer more effectively. This approach differs significantly from current immunotherapies, which typically target proteins or genes.

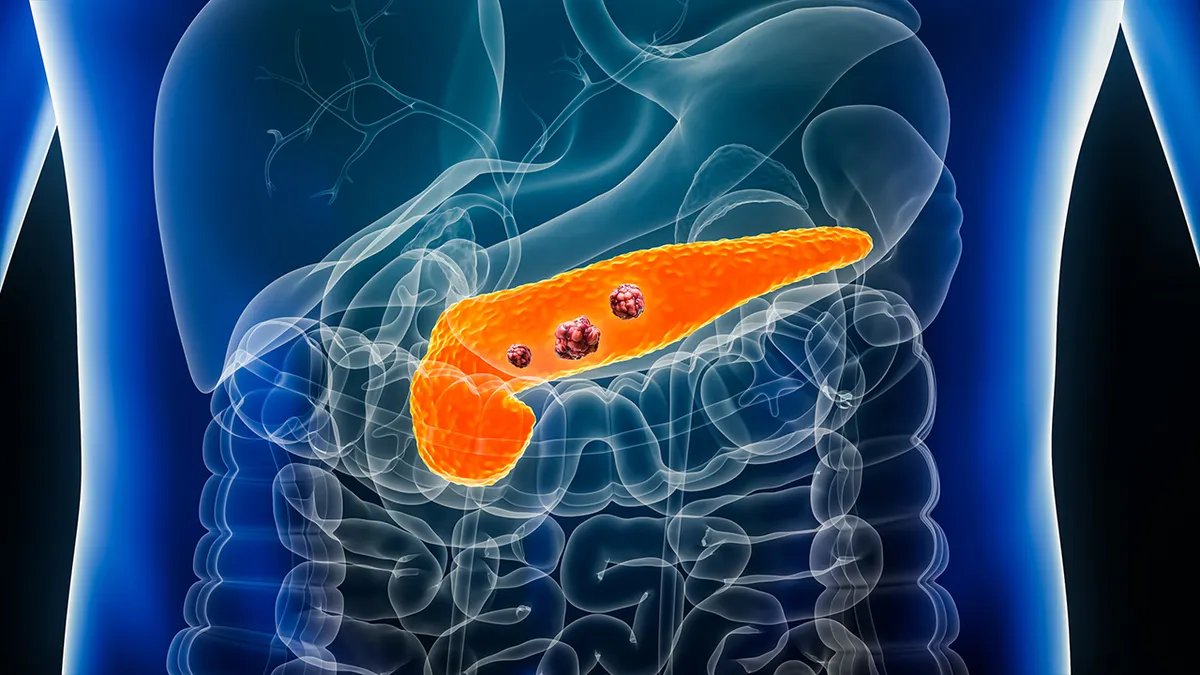

Pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to treat due to its aggressive nature and resistance to many conventional therapies. One reason for this resistance is the unique way pancreatic cancer cells disguise themselves. These cells coat themselves in a sugary layer, effectively tricking the immune system into ignoring them. This new immunotherapy approach aims to strip away this disguise, allowing the immune system to identify and destroy the cancer cells.

Targeting Sugar Shields: A New Approach to Treatment

The innovative aspect of this new pancreatic cancer treatment lies in its focus on the sugars on the cell surface. While most cancer immunotherapies target proteins or genes, this therapy blocks the sugars, essentially removing the cancer cells’ cloaking device. By doing so, it exposes the cancer cells to the immune system, allowing immune cells to effectively find and attack them. This strategy shows promise in overcoming the limitations of previous treatment approaches.

This breakthrough could represent a significant step forward in the fight against pancreatic cancer. By “waking up” the immune cells, this treatment could provide a more effective way to target and destroy cancer cells, potentially leading to improved outcomes for patients. Further research and clinical trials are needed to fully evaluate the effectiveness and safety of this new therapy. The potential benefits of this approach are significant, offering a new avenue for treating this challenging disease.

How Does This New Treatment Work?

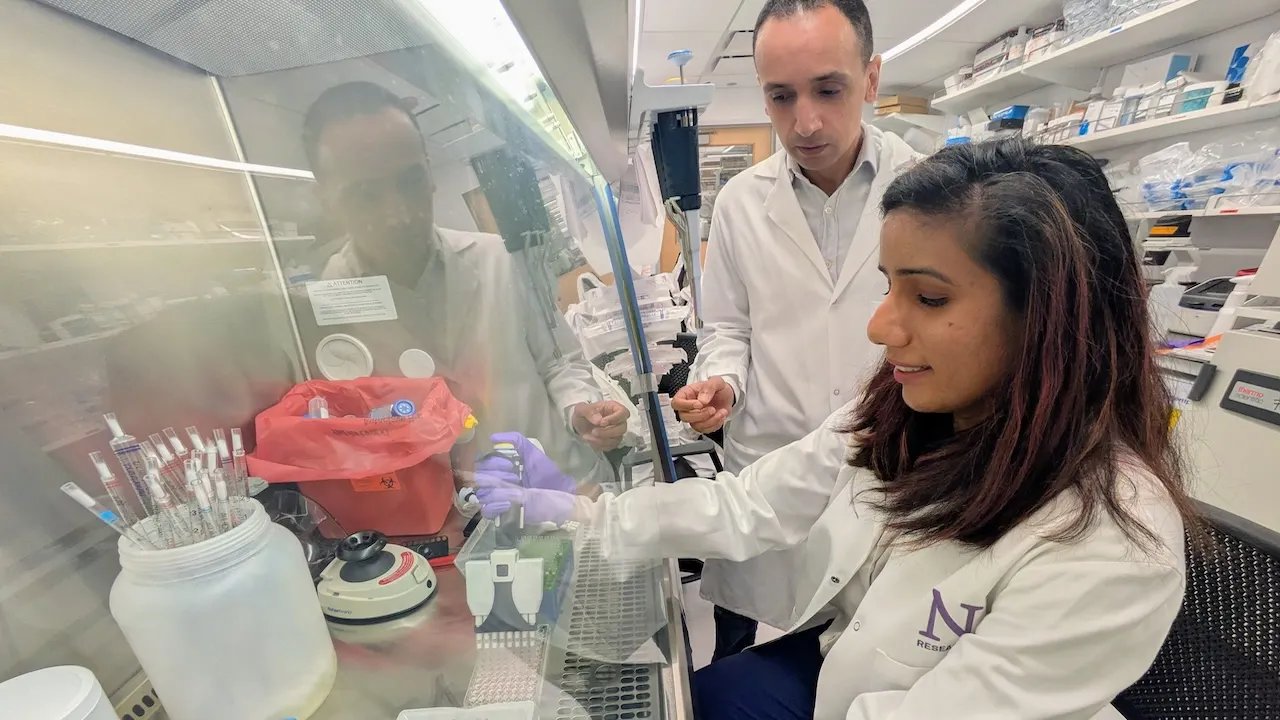

The therapy involves using a specially designed antibody that binds to the sugary coating on pancreatic cancer cells. This binding action disrupts the cancer cells’ ability to evade the immune system. Once the sugar shield is blocked, immune cells, such as T cells, can recognize and attach to the cancer cells, initiating an immune response that leads to the destruction of the tumor. This targeted approach minimizes damage to healthy cells, reducing potential side effects.

The development of this new pancreatic cancer treatment underscores the importance of innovative research in cancer therapy. By targeting the unique characteristics of pancreatic cancer cells, researchers are developing more effective and less toxic treatments. This approach offers a promising strategy for improving the lives of patients with pancreatic cancer. The focus on immune cell activation is a significant shift in the treatment paradigm.

Potential Benefits and Future Directions

The potential benefits of this new approach are substantial. By enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack pancreatic cancer, this treatment could lead to improved survival rates and a better quality of life for patients. Furthermore, this strategy could be combined with other therapies, such as chemotherapy or radiation, to achieve even greater efficacy. This new pancreatic cancer treatment presents a significant advancement in the field.

Looking ahead, researchers are focused on further refining this therapy and conducting clinical trials to assess its effectiveness in patients. They are also exploring ways to personalize the treatment based on individual patient characteristics. This personalized approach could further enhance the efficacy of the therapy and minimize potential side effects. The promise of this new pancreatic cancer treatment lies in its ability to harness the power of the immune system to fight this deadly disease. The development of this treatment also comes on the heels of other innovations, like those discussed in recent debates about research funding and priorities. The ongoing success of innovative treatments will depend on continued scientific advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

This article provides comprehensive information about the main subject and related aspects.

Additional information and resources are available through the internal links provided throughout the article.

This article contains up-to-date information relevant to current trends and developments in the field.

This article is designed for readers seeking comprehensive understanding of the topic, from beginners to advanced learners.

Important Notice

This content is regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance for our readers.

Content Quality: This article has been carefully researched and written to provide valuable insights and practical information.